|

Hey everyone # |

|

I’m Dan McKinley. It’s nice to talk to all of you. I’ve done engineering since the turn of the century, and led small teams and biggish orgs. # |

|

I’ve spun the wheel enough times that I’ve gotten a few stretches of my career when things were going great. Nothing gold can stay though, and those moments were fleeting. Welcome to my latest talk in my very-slowly-moving series about trying to rekindle that magic. # |

|

At most places I’ve worked, things haven’t been going great. I’m not really complaining. I was in a position of responsibility at those places, and I hope I did more good than harm. I’m going to talk through some stories about that. My hope with this is to do more good than harm. Maybe y’all can create more fulfilling places to work, and hire me to work there. # |

|

So I have noticed similarities when things are going poorly, and would like to talk about them. # |

|

One big problem everywhere is that once you have two employees, you have to divide responsibility somehow. How you do that is really important. It’s a move that has both immediate and second-order consequences which are mostly awful to contemplate. So most companies don’t contemplate it that much. # |

|

Computer scientists like me start their career by realizing that they accidentally joined a math major that isn’t a science, and isn’t about computers. It’s about how abstract work gets done and stuff. And the trauma of this initial realization is so severe that we spend our entire careers refusing to apply anything we learned outside the domain of computers. Things might be better if we tried to think about work as much as we think about the computers. Later in this talk I will try, despite how much it hurts me to do that. # |

|

I’d like to talk through the dynamics I’ve seen at different places. I’m going to anonymize it somewhat because even really successful companies suffer from pathology, and my intent is to learn rather than just shitpost. # |

|

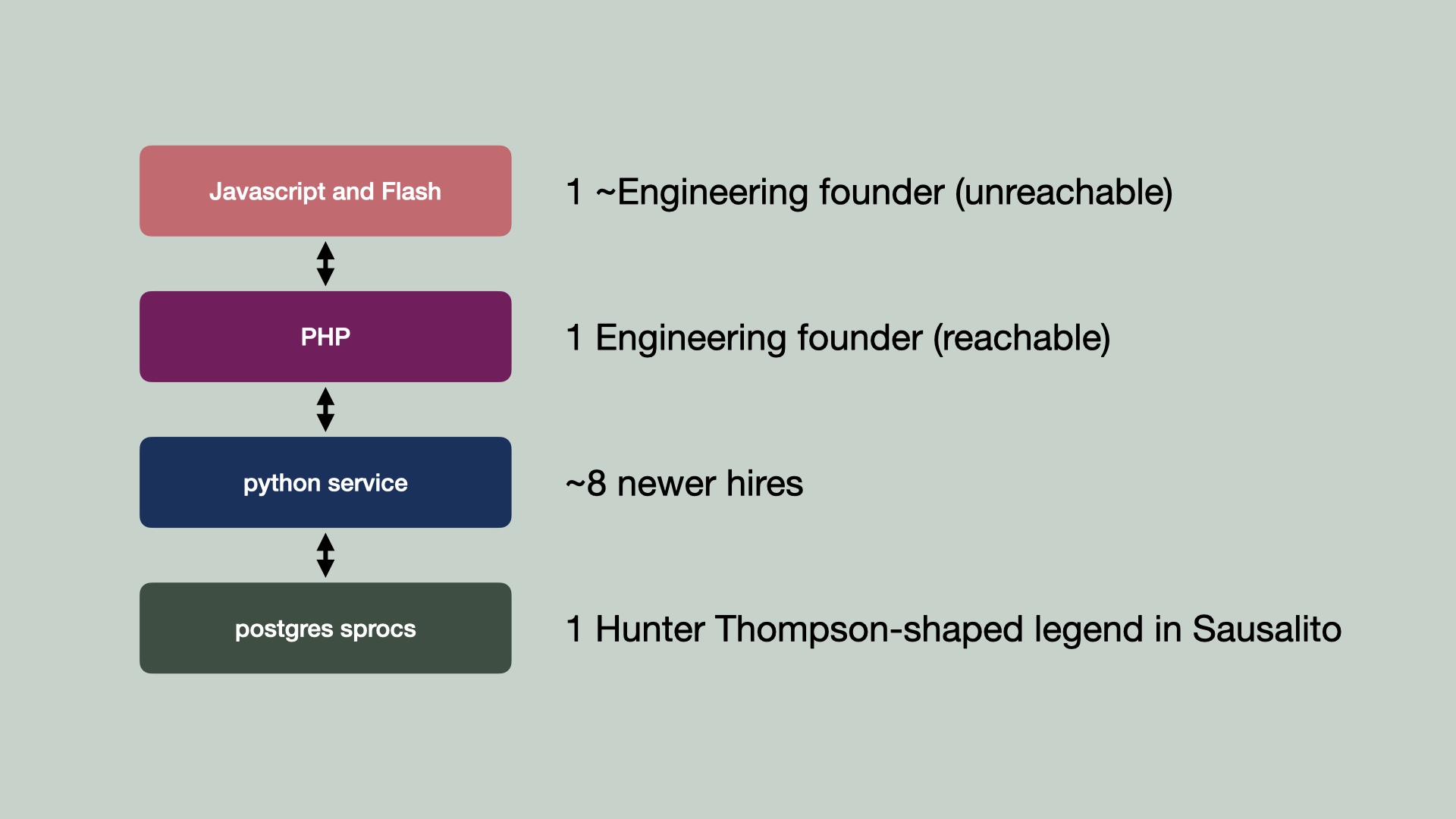

The first job I want to talk about was a startup I worked for, which ultimately was really successful. I was in the first 20 employees there. # |

|

You’d think this would be a really scrappy group but no, at that point they had already managed to set themselves up like IBM in the 1970s or something. I was hired to work on a python middle layer which should not have existed in the first place. In this misguided attempt to scale, they added a Python middle layer. The theory was that web requests would be served faster if they progressed through more network hops. This is a bad theory. # |

|

So to launch any feature at this company, you needed to get a database person to do some DDL and write some stored procedures. You needed to get a python person to write some python that didn’t achieve much. You needed a PHP person to write some frontend code. And so on. As a result of all of this, the company released zero features for two whole years and everyone got fired. (But not me, I survived by complaining.) # |

|

Much later on I worked at a fairly mature company that had more than a thousand people and was selling a b2b product. # |

|

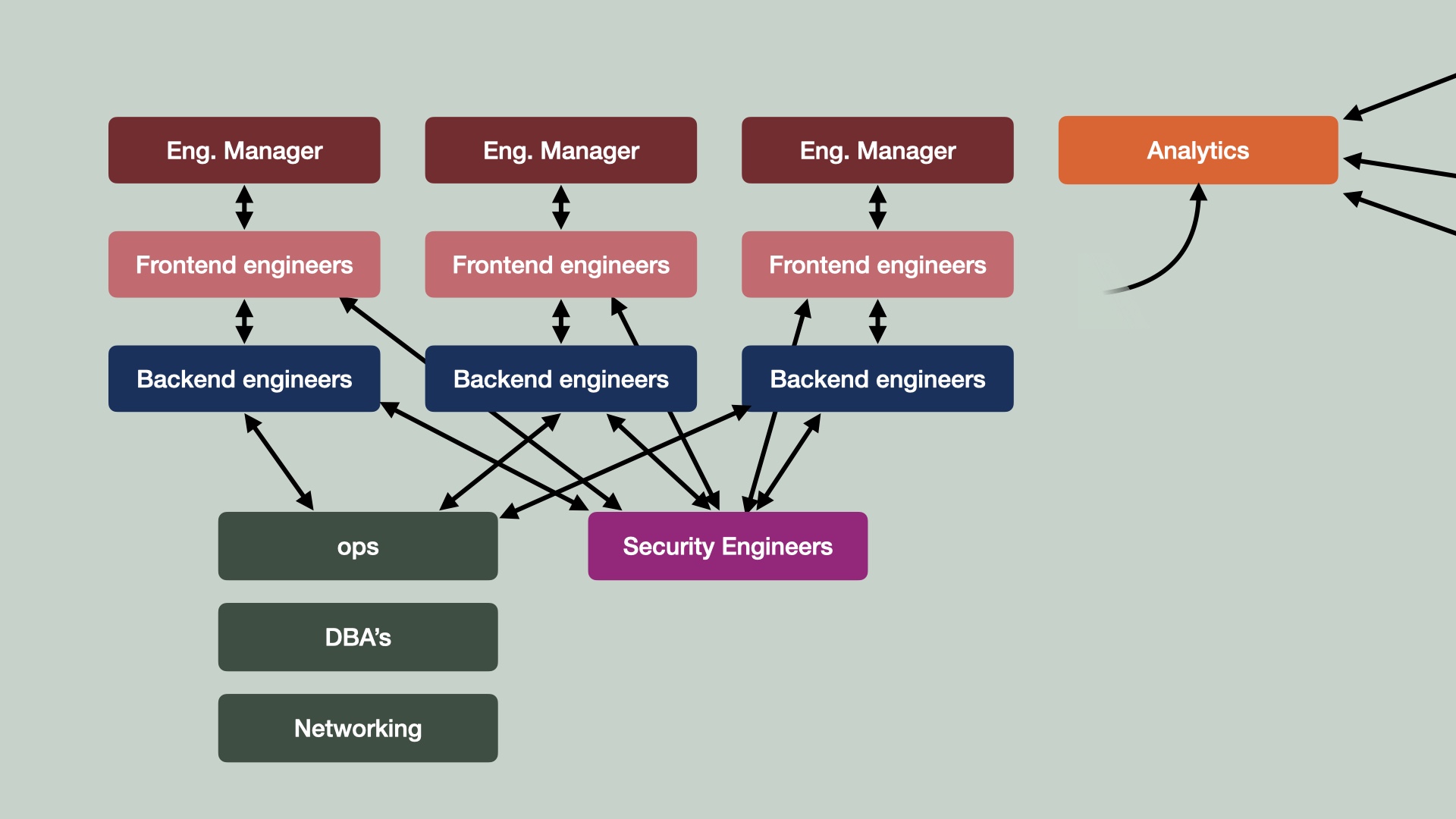

They’d managed to avoid serializing absolutely everything, in that they’d divided into feature teams. And they had shared services teams like ops, and DBA’s, and so on. That seemed reasonable at first, or at least not different than most places. # |

|

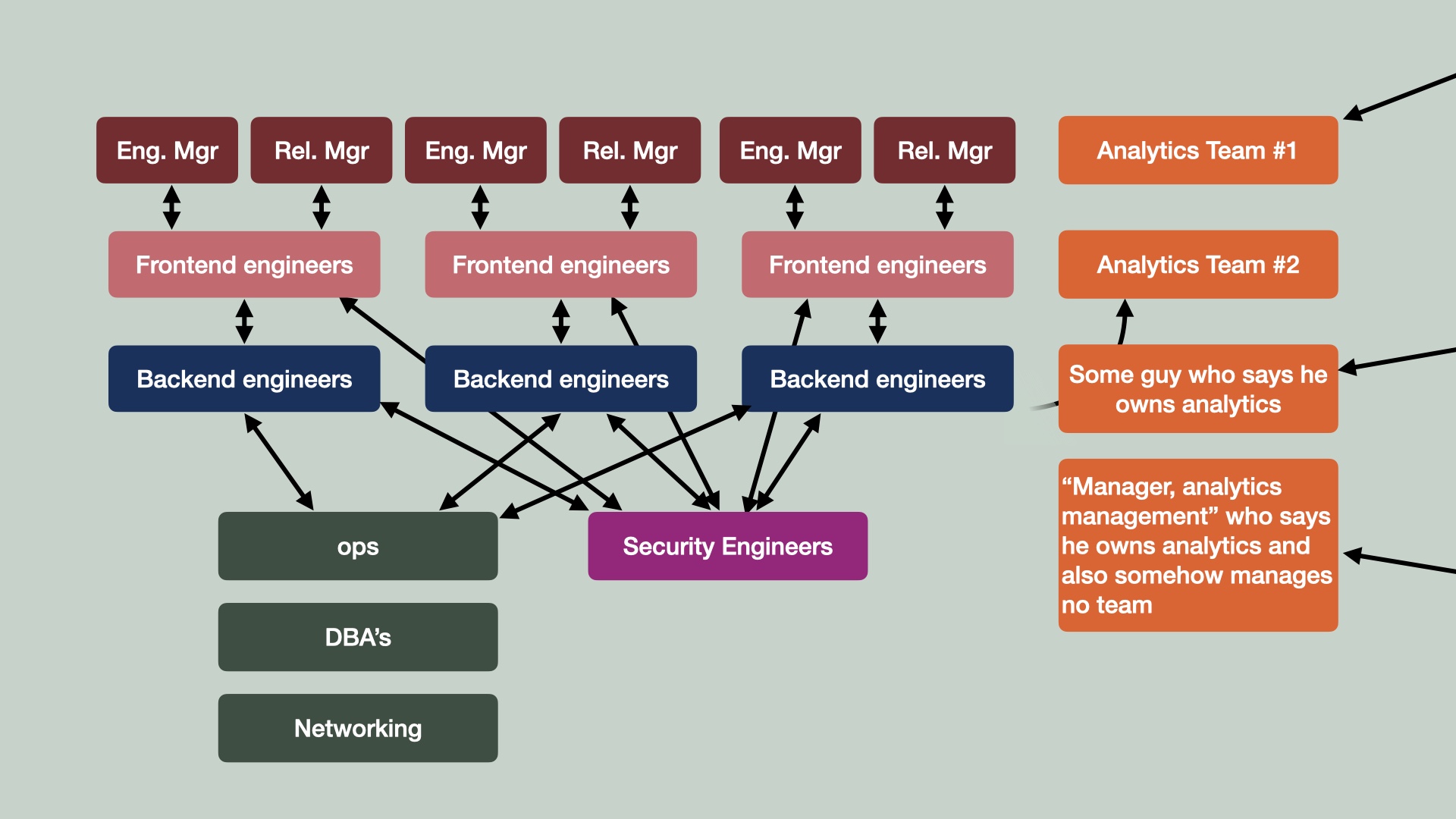

But something interesting had happened where the roles just kept dividing, like a bacteria colony out of control or something. They split engineering management in half and created a role called “release manager.” To … manage releases, I guess? It was never entirely clear to me why. At some point things just came unglued. # |

|

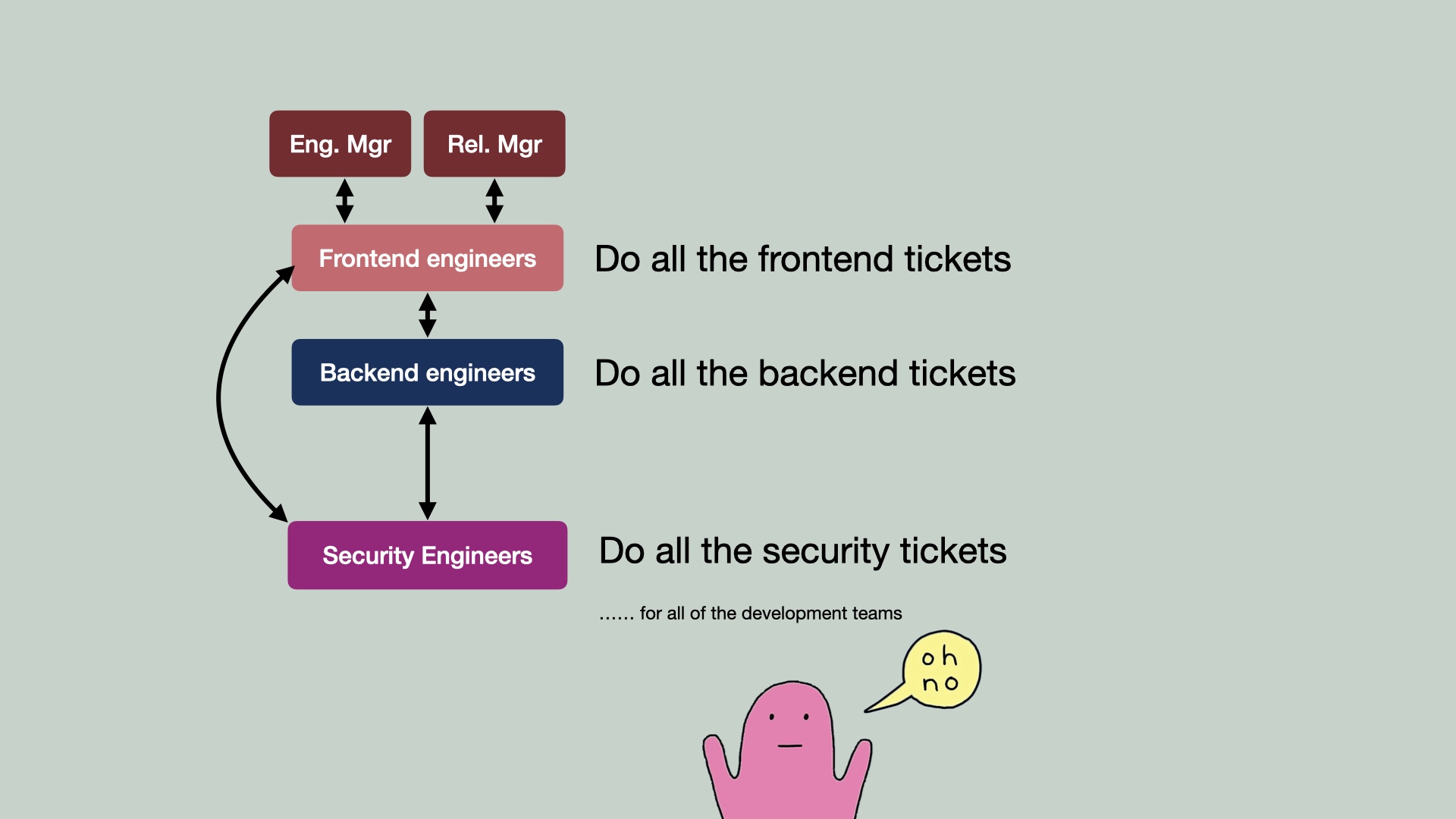

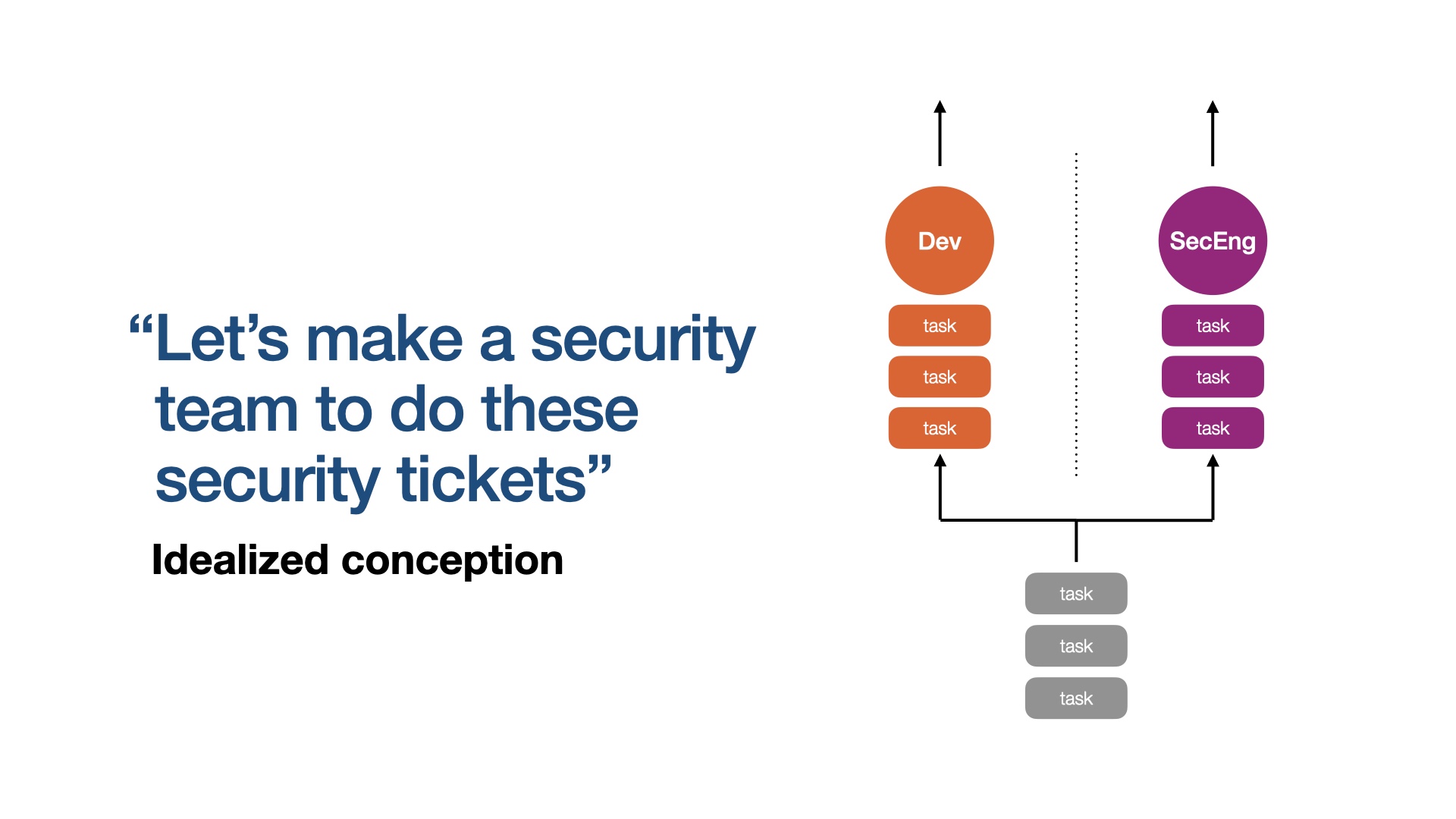

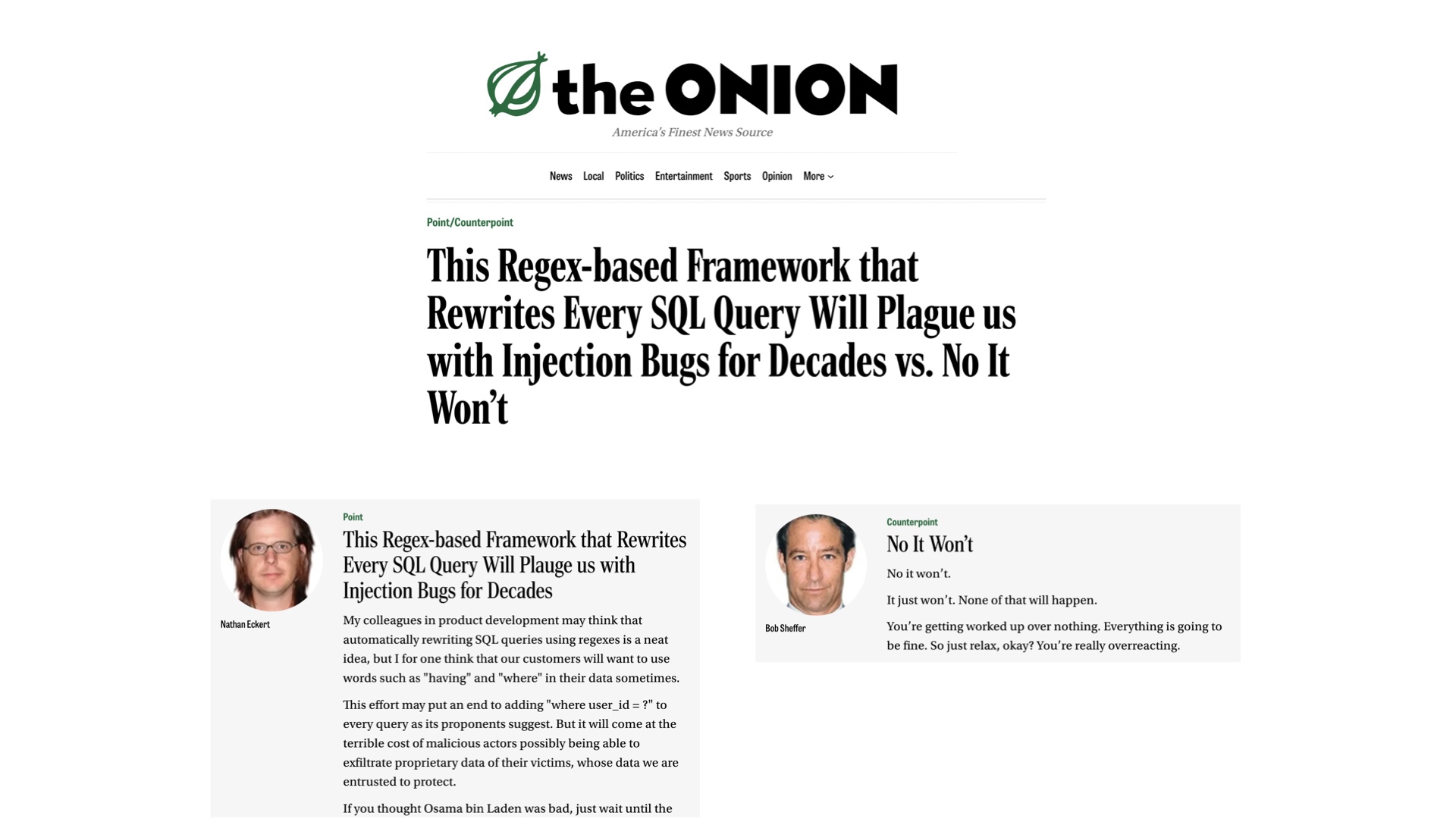

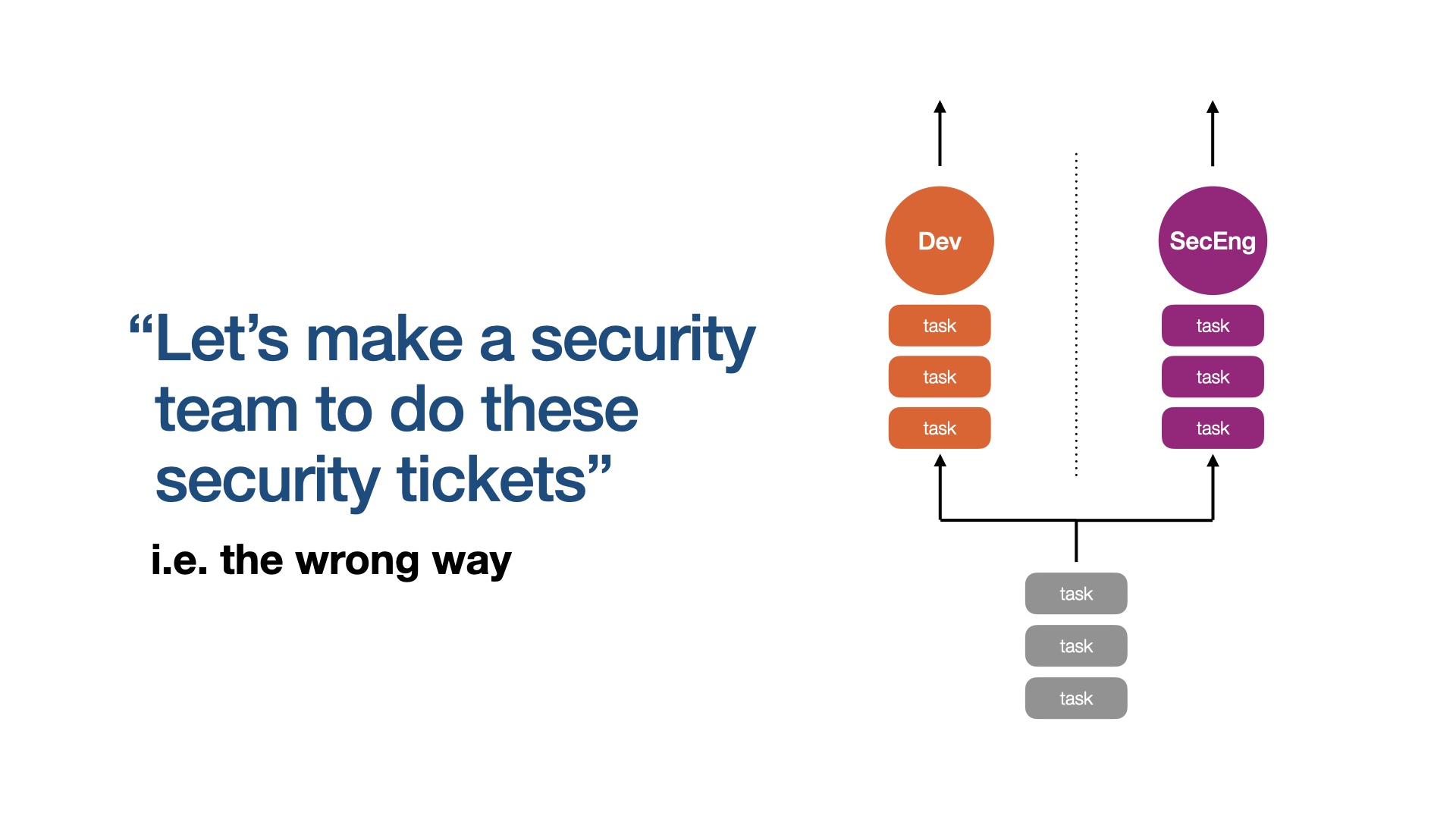

And they chased that dragon into some very dark corners. A big mistake they made in my view was that they conflated roles with work a little too much. Frontend engineers did all of the frontend work and none of the backend work, and vice versa. That was survivable, but taking that policy to the security team and making the security team do all of the security work was not. I’ll come back to this. # |

|

And then finally I worked at a company that mostly made native client applications. There was initially one big hit client app, but by the 2020s a bigger, disjointed set of efforts had grown up in parallel. # |

|

The product portfolio as a whole had a very weak supervisory structure. The products didn’t coordinate in any meaningful way on tech stacks or other decisions, since they all independently reported up to a CEO that made no attempt to coordinate them. But despite that, an attempt was made to have a shared operations function. This presented a lot of difficulty because the operations group wasn’t involved in architecture decisions. They wouldn’t have had enough time to do that anyway, since they were busy with hundreds of services that dev teams had moved on from years before. It’s a tale as old as time. # |

|

So that was a high-level overview of how all struggling companies are unique. But they’re also all the same. I’ve spent many nights pondering the mistakes these places have made, and I’d like to inflict my observations on you now. # |

|

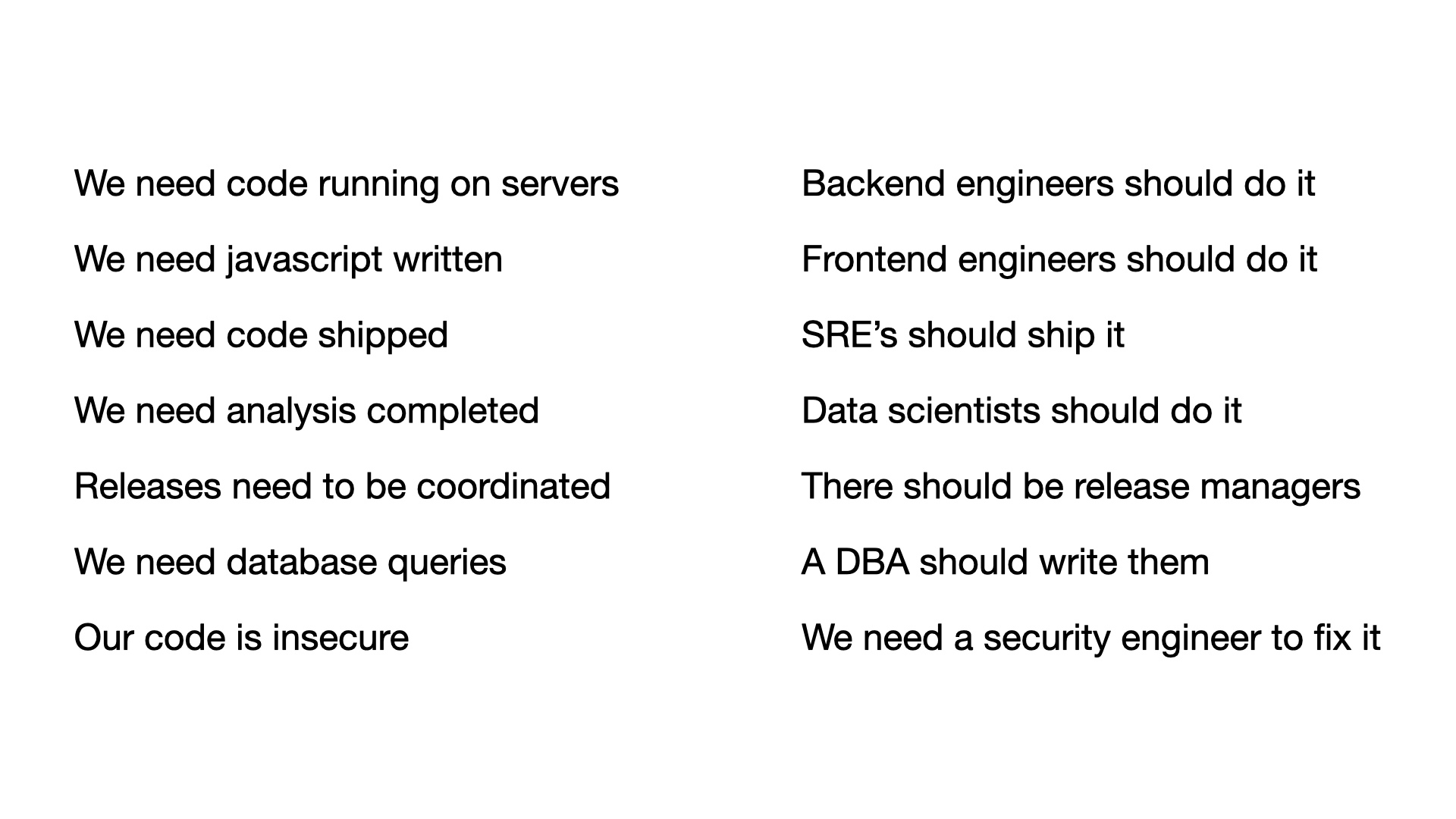

One big thing that a lot of people love to do is create new role types. For any new thing a company wants to do, the tendency is to put up a new job description. # |

|

I think a lot of people notice this and chafe at it when the role is for the new hotness. For example, every company wants to rub some AI on their stuff now, so they are putting up job descriptions for AI engineers. If you’re an engineer interested in AI sitting in such a company, you’re annoyed that they’re doing this (and potentially paying that person more than you) when you could easily rub some AI on some stuff. This is just a salient example of a dumb mistake that happens in many, many more dimensions all the time. # |

|

A mundane example of that is the ops and development divide (or these days maybe the divide between SRE and development). That divide has been very pronounced at nearly every place I’ve worked. # |

|

And that’s despite every single one of those companies claiming that they quote-unquote “do devops.” Devops as a portmanteau was meant to communicate something about breaking down the divide, and building empathy between these two groups. I have worked hard to cultivate this, personally, but rarely found it in the wild in reality. # |

|

Once people have subdivided work, they naturally try to arrange people into assembly lines. If you have AI work, hand it over to the AI person. If you have ops work, give it to the ops person. That’s the kind of thing that feels obvious to leaders, but I think it’s wrong. And sometimes it’s wrong in a mathematically provable way. Let’s dig in. # |

|

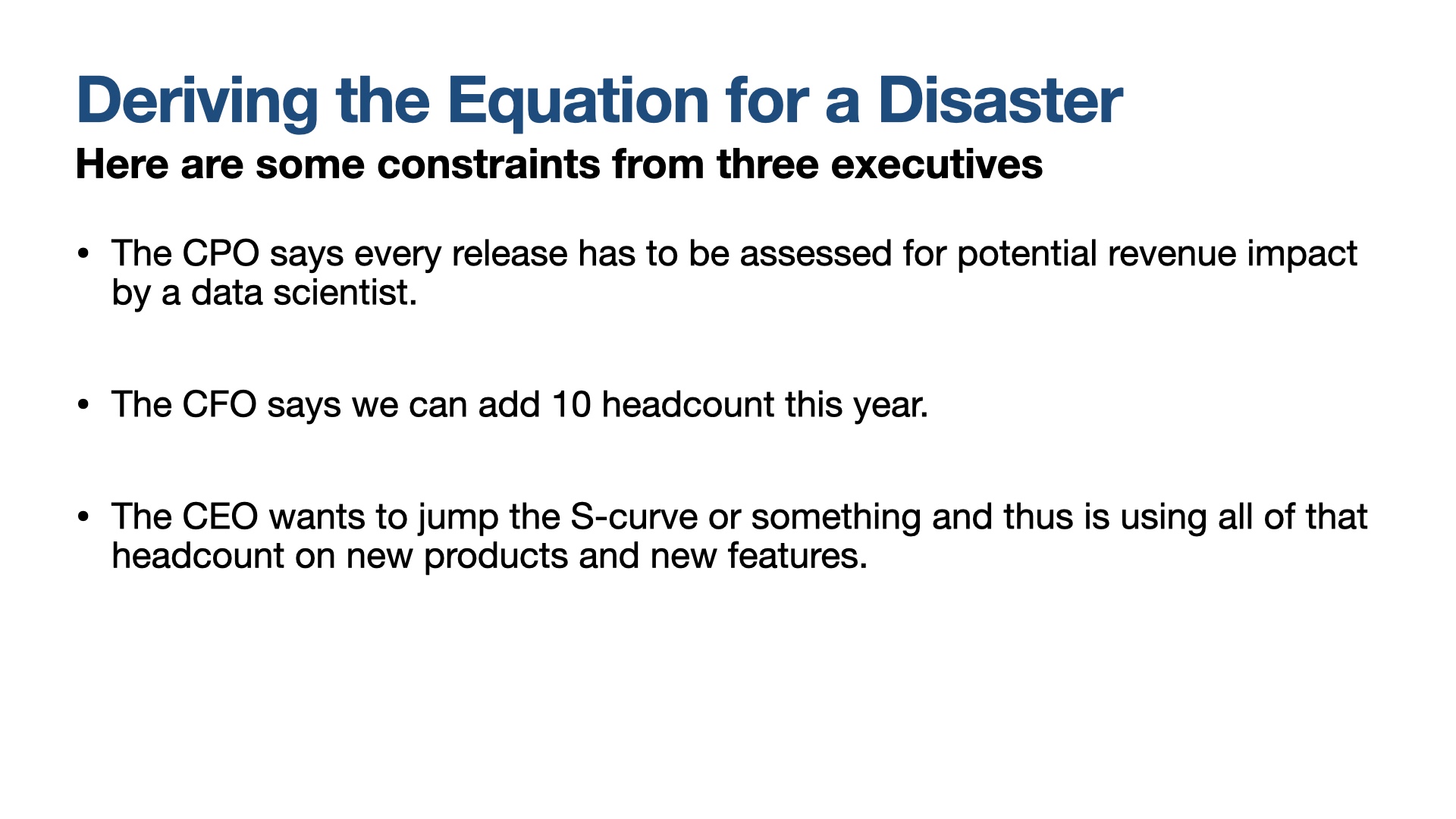

Here’s a very typical set of executive constraints. They might say: we have to measure everything. We aren’t going to hire more data scientists. We’re going to focus on building new products and only hire new engineers for that. # |

|

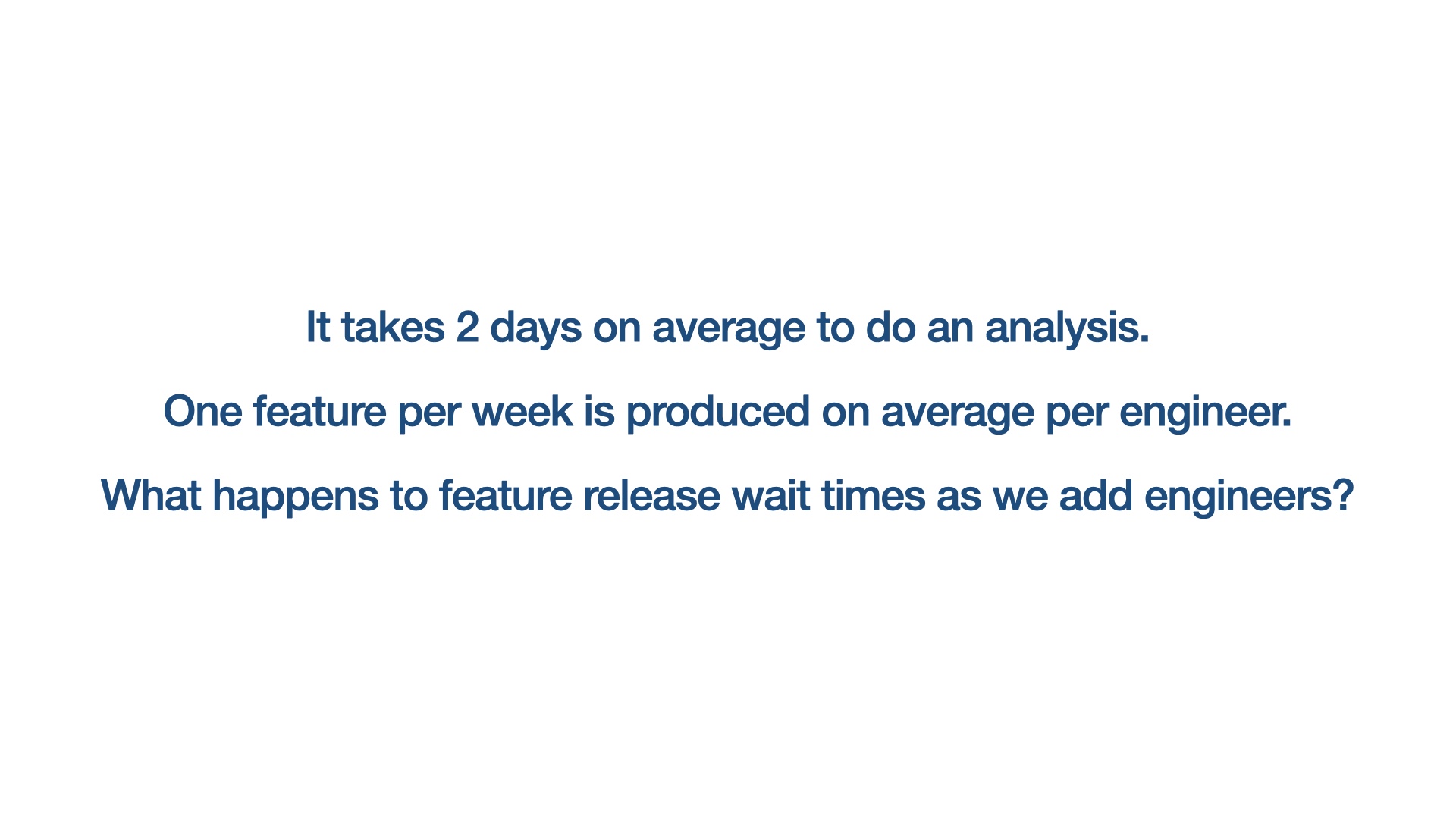

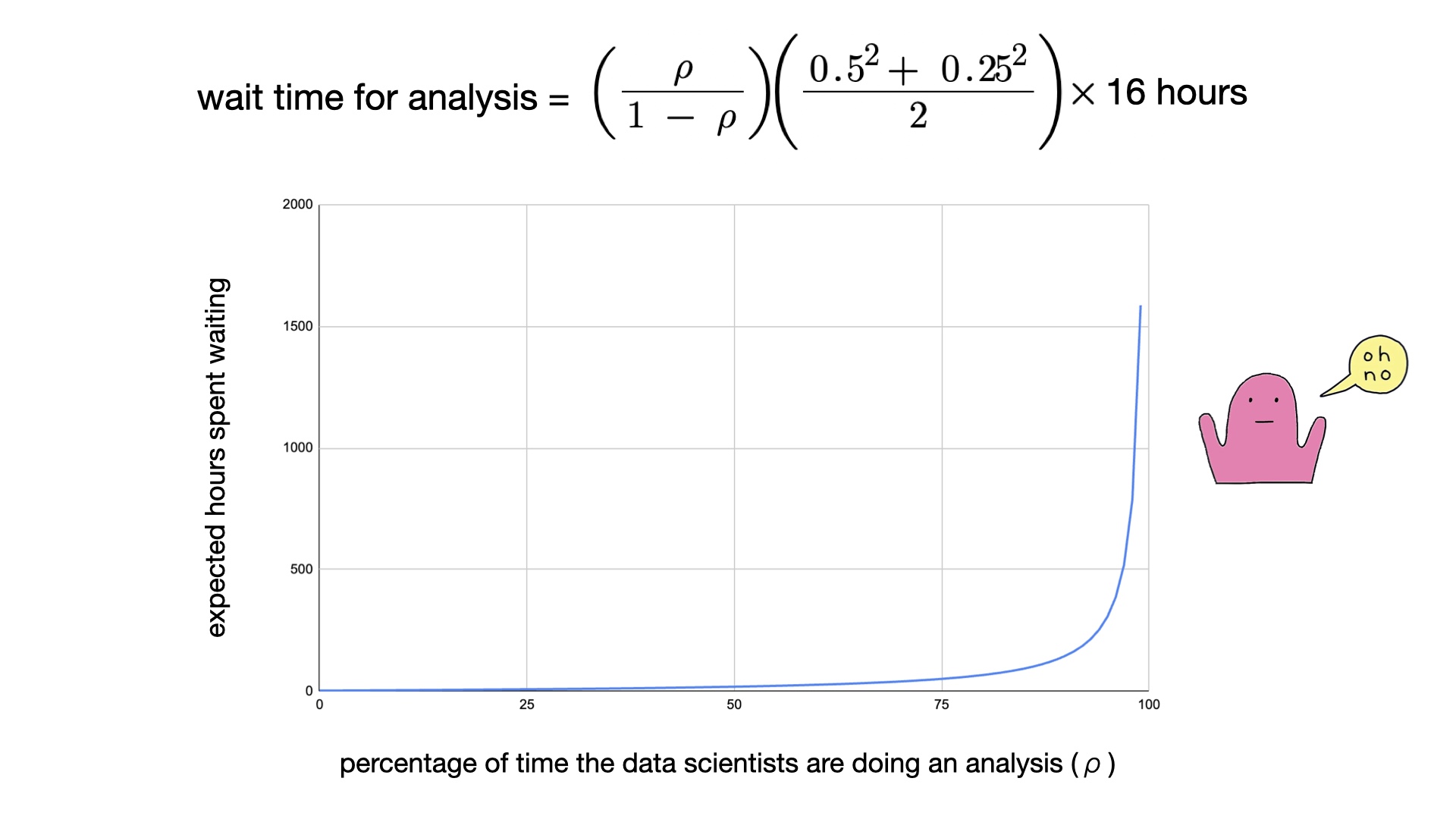

Those are inputs to a very simple equation. Engineers produce work that needs to be analyzed at a rate, and the analysis takes a finite amount of time. Remember the premise is that we are trying to go faster by adding engineers. # |

|

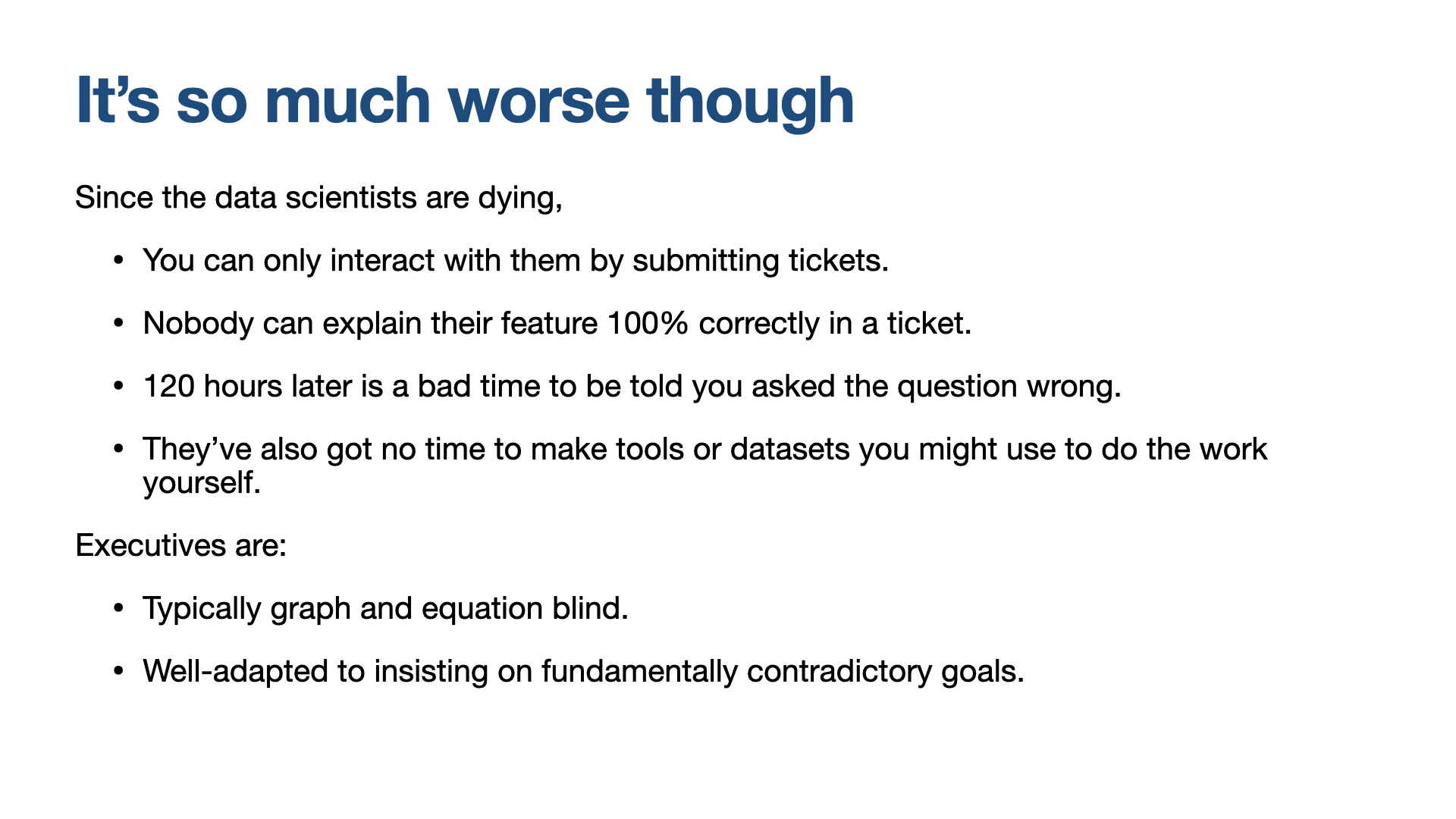

But, whoops! We made everything go slower, actually. With that simple setup, it doesn’t take very long at all for things to get extremely out of hand. We added a few engineers and wound up with a nonlinear increase in how long people need to wait before they can ship things. By the time the data scientists are fully busy, the individual feature waiting for analysis is absolutely doomed. (Source for the math is here.) # |

|

Of course, organizational dynamics are stacked against analyzing this

problem in a clearheaded way. Everyone thinks the other groups are

sandbagging. We come into petty conflicts that obscure the physics

of the situation. # |

|

That kind of setup is one in which ticketing things can generate more work than you’d have if people had time to talk to each other. That’s a specific case of a general issue. Poorly factored organizational boundaries create work. # |

|

Earlier I talked about a company that tried to use its security team to do all of the security remediation work. By adding a queue for security tickets, they were hoping for a result like this. There’d be the same total volume of work getting through the system, and fewer context switches. # |

|

The problem with that is the horrible things development can get up to when it’s not encouraged to worry about security. # |

|

We can generate extra security work with our engineering activity if we erect a wall between those things. On a long enough timescale of course something horrible precipitates, but that’s a problem for future you. In the here and now it’s only a minor humanitarian catastrophe which we can ignore. # |

|

An undercurrent of all of this is how people conceive of themselves, and how they are to one another. # |

|

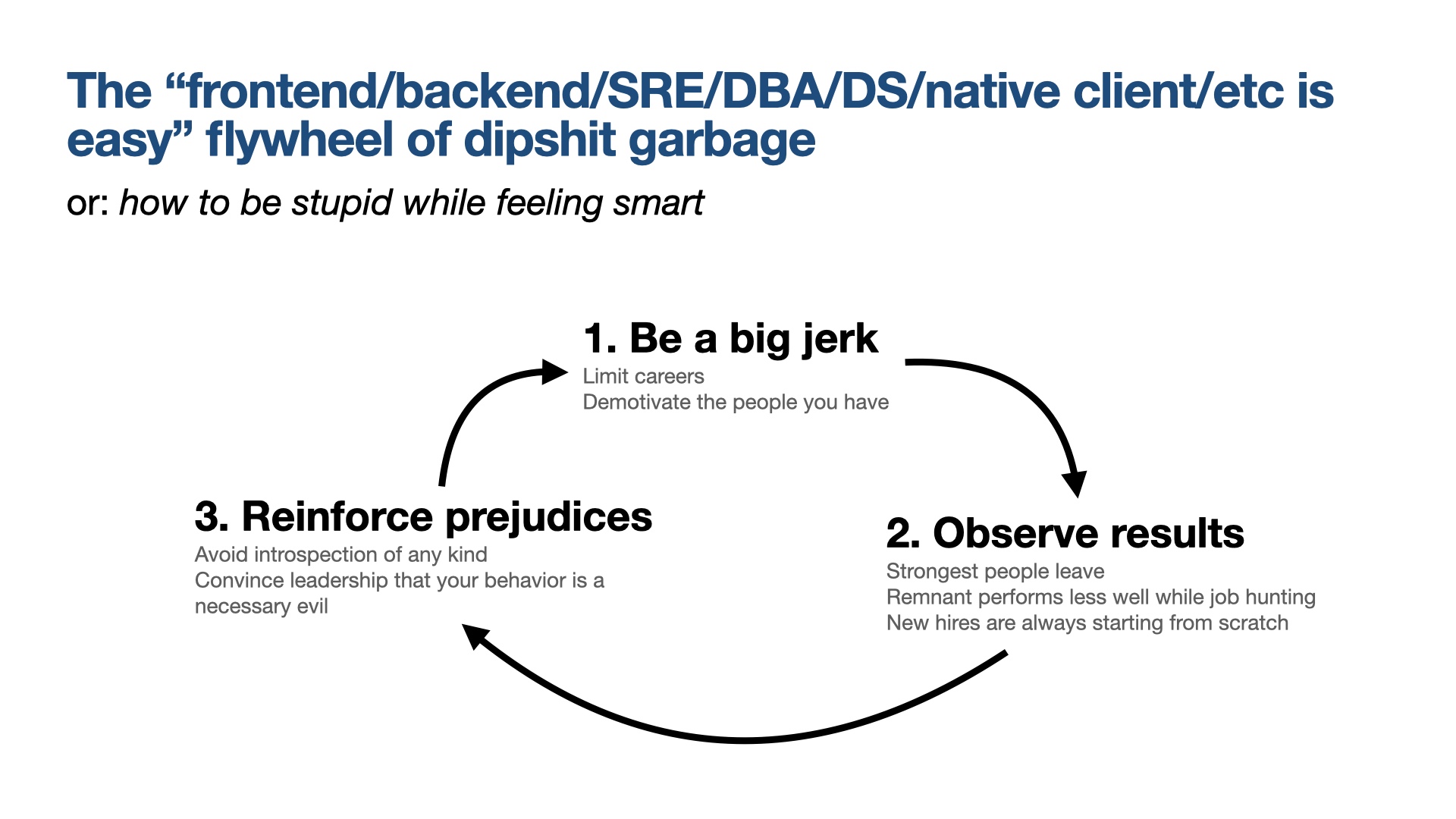

There can be a general tendency among some of us to imagine that other peoples’ jobs are easy compared to ours. Obviously it’s not a majoritarian view that working on the server is so easy “it’s not clear it’s even technical,” but I can report that some crazies out there do hold this view. # |

|

Those vibes can absolutely run in the other direction though, and thinking that product work is less technical might be even more common. Platform teams are full of folks who aren’t very worried about what the company they work for even does. # |

|

Although the results of these tendencies are very stupid, punting the offenders into the sun usually eludes us a solution. That’s because this behavior can be coded as “smart” and “valuable” to outside observers. While a CEO may not endorse the behavior, they imagine that it gets results. Except it doesn’t. Driving other workers out reduces total throughput. Obviously. The biggest problem with brilliant jerks is not necessarily even that they’re jerks. When you take a systemic perspective, they aren’t even brilliant! They’re dumb! # |

|

Recurring themes throughout every chapter of this for me are parochialism and ego, the yin and

yang of dysfunction. Both of these have positive and negative spins. Parochialism might be deference, and not wanting to step on someone else’s toes. Or it might be lack of curiosity. Ego might be pride in your work, or it might be territoriality, or dismissiveness in the abilities of others. These are the primal urges that lead to the breakdowns in empathy that fill our lives with pain. # |

|

Thank you for allowing me to trauma dump for a while. Like I said at the beginning of this talk, I’m motivated to make things better, not just complain. I’ve spent a long time thinking about how the most functional engineering team I ever worked on got that way, and I want to give you a vignette from those times. # |

|

The startup I worked at fought its way from horizontally layered fiefdoms to a simpler architecture and a smaller team. We imported some leaders that took devops very seriously, as they had come up with the idea in the first place. The most important bit that we took from that movement was that we should tear down existing barriers between roles. So after about two years of creative destruction pretty much everybody was pitching in on pretty much everything. # |

|

That approach was ultimately successful, and we found infrastructure stability and gained some ability to ship software again. We crawled out the other end of the scaling tunnel clean. # |

|

That, combined with several CEO changes due to some other chaos, morphed the company into an engineering-led organization. As an engineering team we found ourselves reaping an infrastructure dividend that gave us a bit of free time, and we had an unusual level of permission from the rest of the company to dictate how that time was used. # |

|

That’s a rare situation, and I think we knew it at the time. Ideas were thrown around about how we should use our extra capacity. # |

|

I’ve been part of several other teams that found themselves in this situation and decided to rewrite various things they hated. I think this is the most common outcome. But we had already tried this, so it wasn’t popular. # |

|

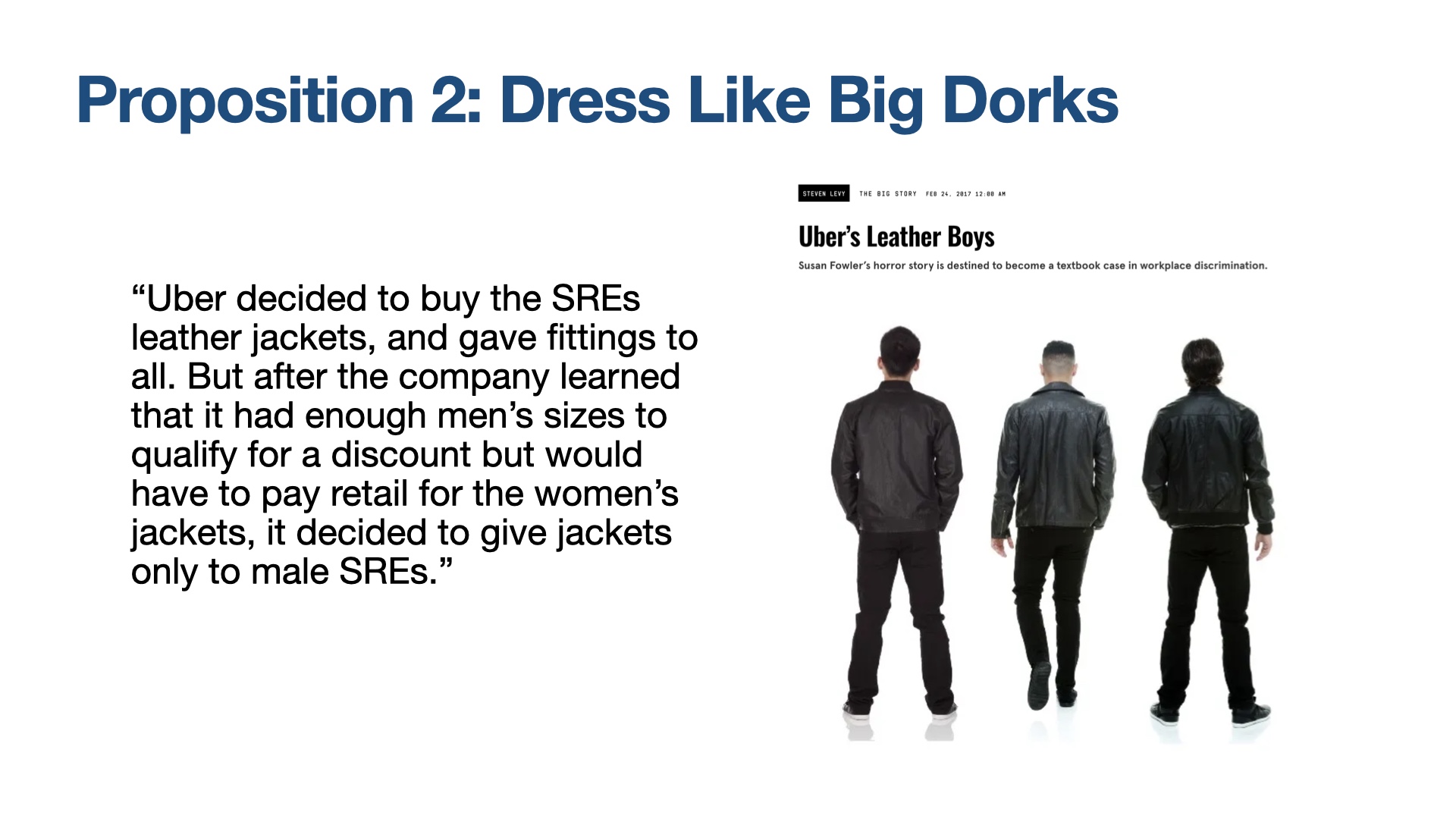

The other thing people seem to do in this situation is buy merch and strut. We did a bit of that, but not as a primary strategy. # |

|

None of that felt right. It just wasn’t us. So we didn’t do anything drastic for a while. # |

|

Then one day, our designer broke the build in the middle of the night. Everyone came in the next day and couldn’t work until they figured out what had happened. # |

|

He was obviously really apologetic about the whole thing. An apology email thread ensued. # |

|

The temptation was there to be huge jerks, and rebuild fiefdoms. Perfectly reasonable people thought that maybe we should put more of a wall between designers and the css source code. It was suggested that designers should just design, and coders should do all of the coding. # |

|

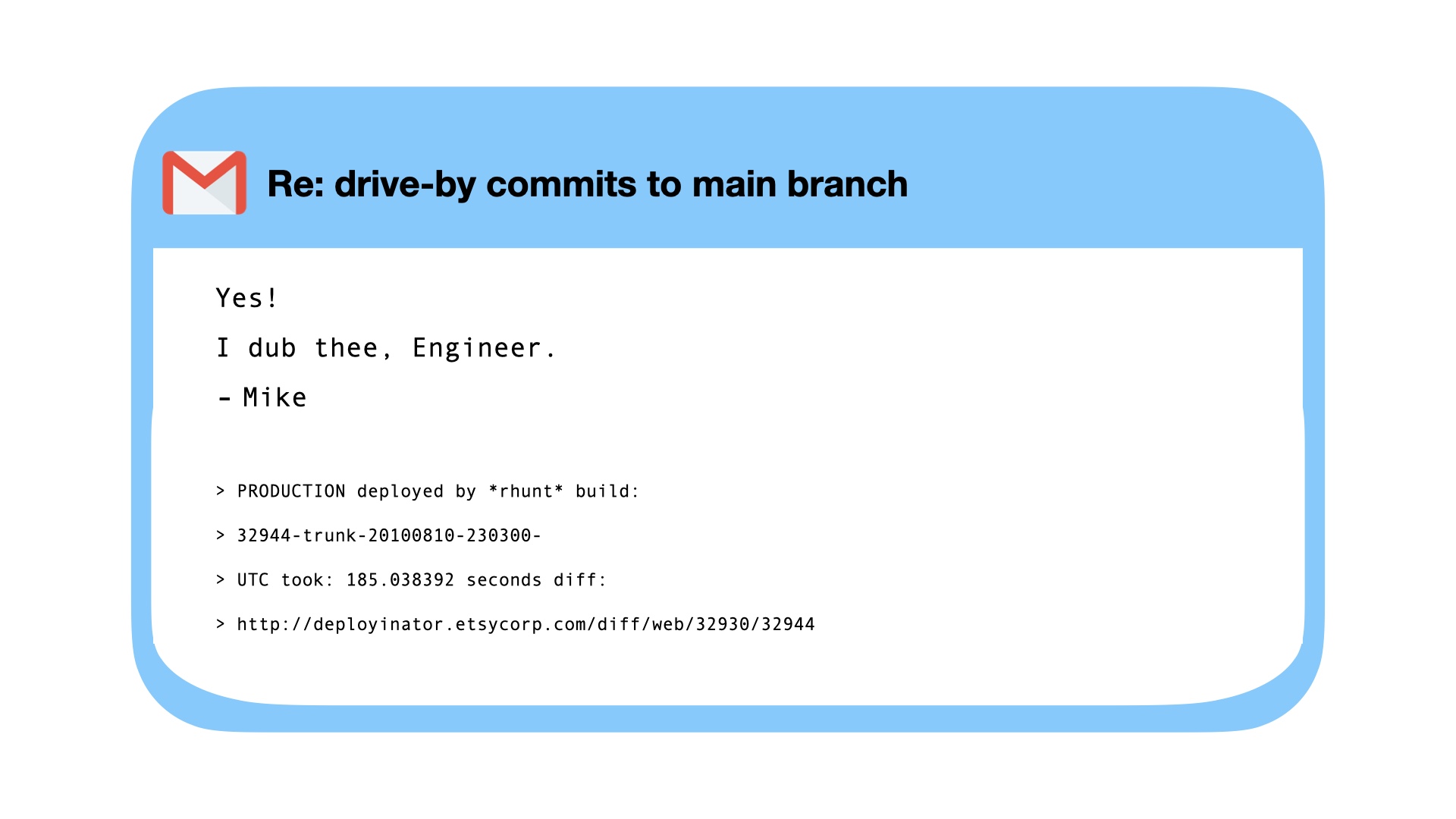

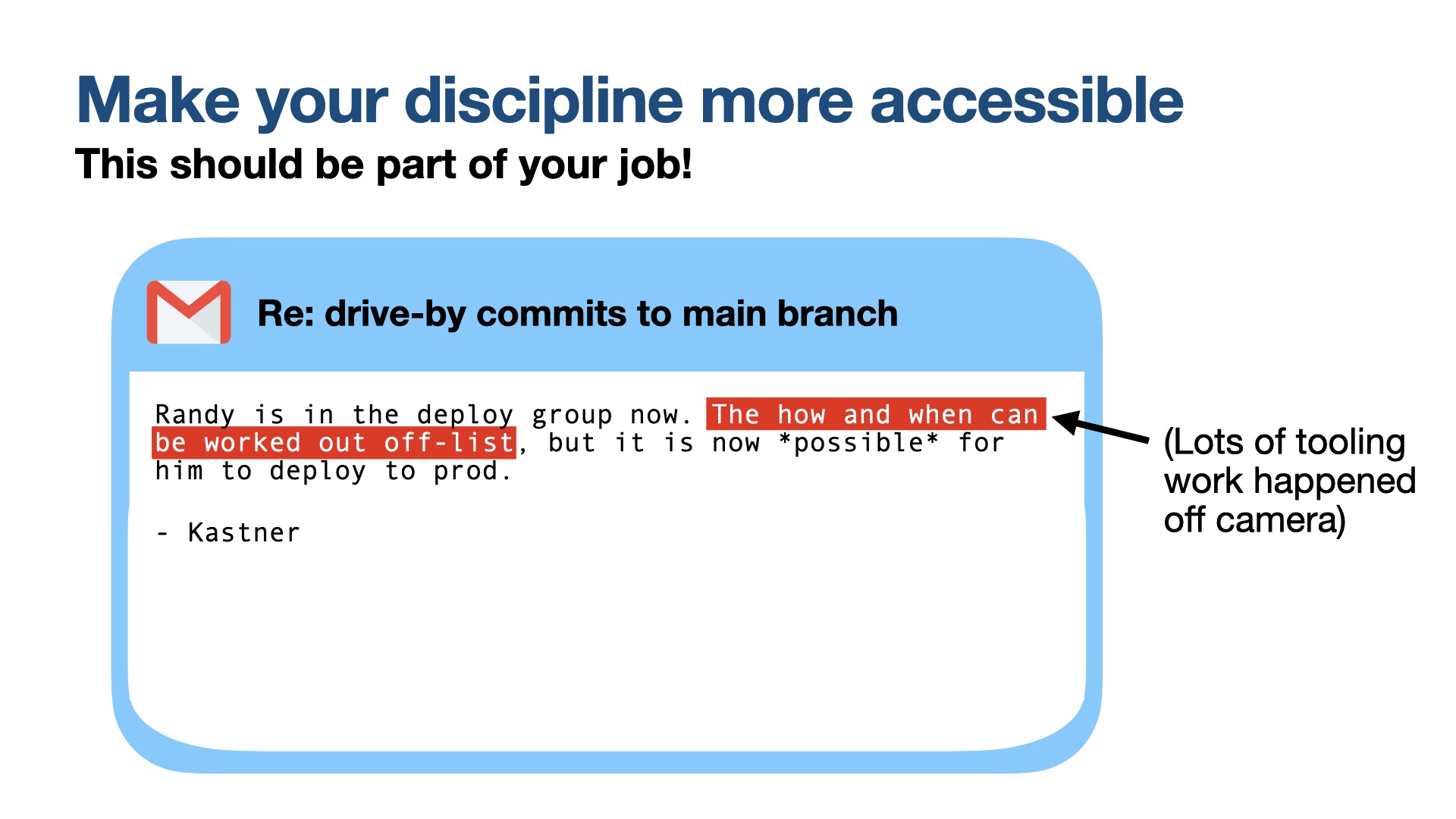

But instead a miracle happened. There was an inspired person who decided to do the opposite. They just yolo’d giving the designer the deploy keys. I’ve come to understand this event as being entirely contingent, but it was also very special. # |

|

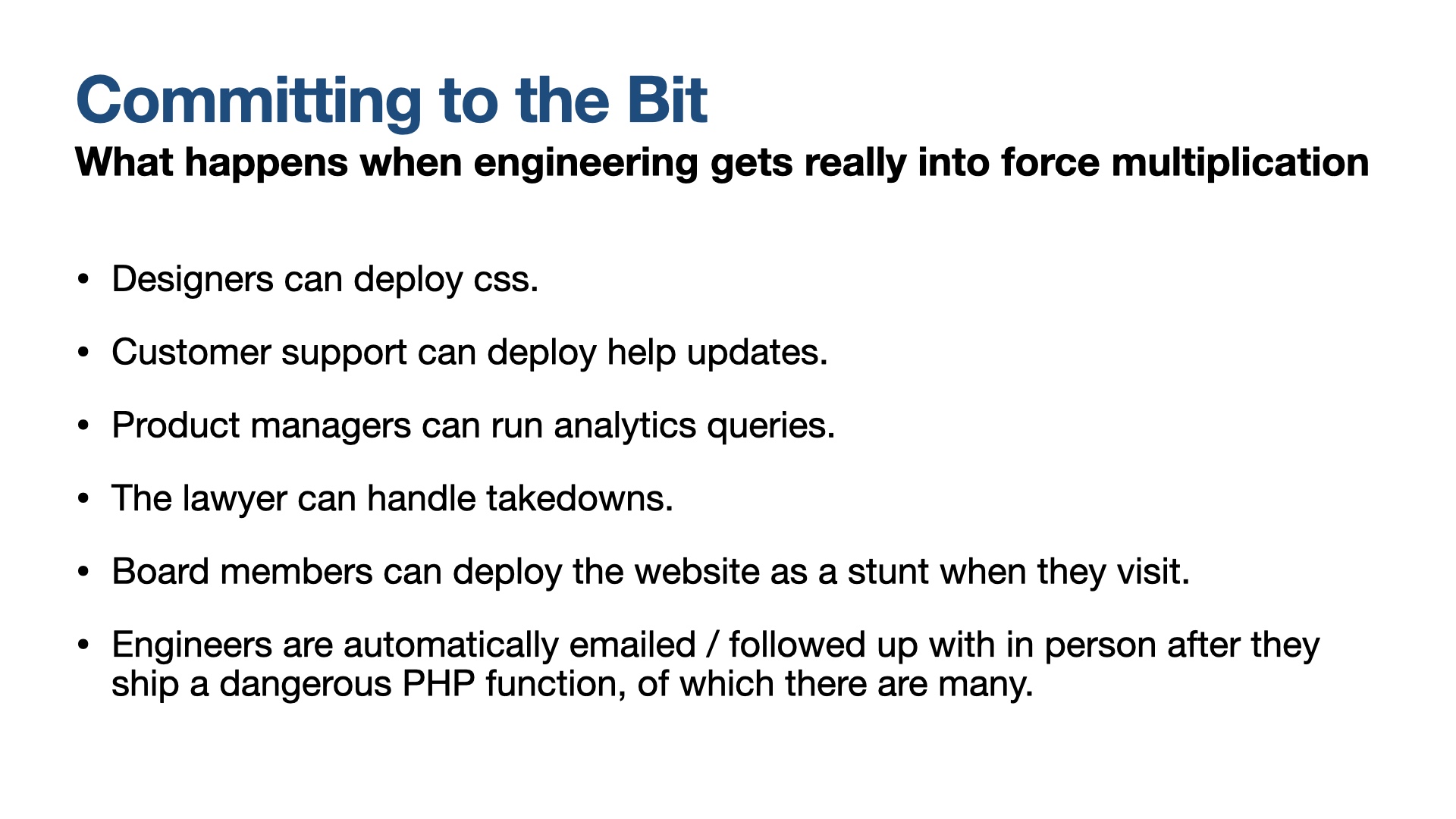

And it was great. Designers started shipping code. We spent our free time building everything we needed to in terms of monitoring, test suites, et cetera to make that safe for them to do. Everyone rejoiced and got shit done. Nothing bad happened. # |

|

That was an epiphany: the thing we were actually going to do was use our rare and precious organizational power, and the free time that came with it, to lift up other teams and make them more effective. # |

|

There were a lot of epiphanies in that era but they all kind of felt like that one. We did the thing we did with designers with tons of other groups, in technical and nontechnical disciplines. # |

|

That was the process of getting from a place of not executing to executing really well. I want to spend a bit of time talking about what good felt like. # |

|

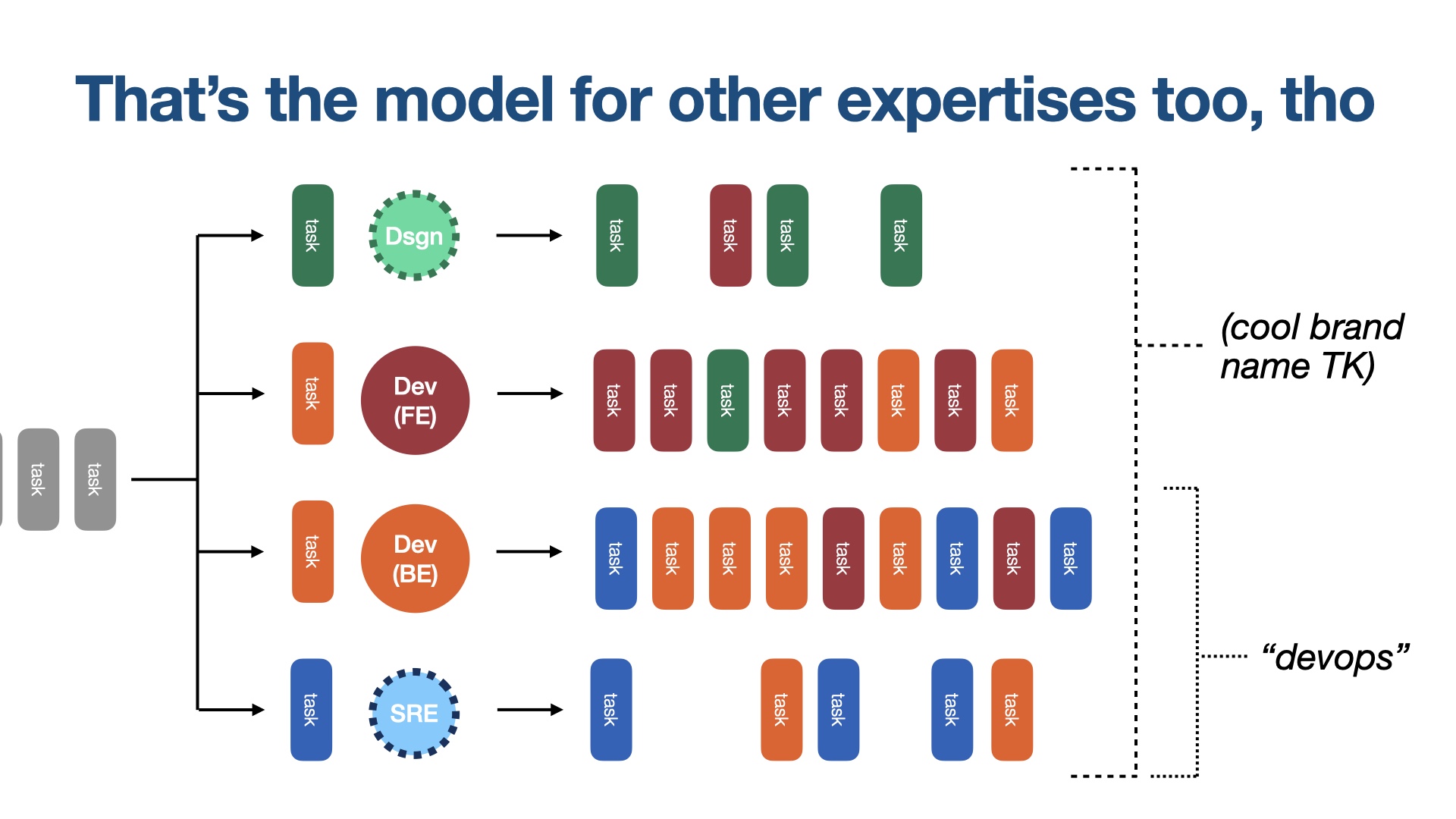

We tried really hard to have domain experts, but never really domain owners. # |

|

Let’s go back and consider the company I worked at where the security team was responsible for all of the security tickets, again. # |

|

The way we approached that when we were executing well was that everyone was responsible for security. The security team was the set of domain experts focused on leveling everyone up in that regard, and making sure we all got to a secure place. (I think this is thankfully not that uncommon when it comes to security as a discipline.) # |

|

But it’s a lot less common in my experience to buy into that model for other disciplines. We had a word for the idea that SRE and developers should share tasks, it was “devops.” But like I said nearly all teams I’ve worked on since have not actually done this. And many teams I’ve worked on have also failed to extrapolate, and have had frontend or client engineers strictly siloed from backend engineers. They get up to building entire GraphQL monstrosities to avoid talking to each other. You want someone that’s an expert in frontend work, but I think you probably do not want people with “frontend” and “backend” in their title. # |

|

Domain experts, not domain owners. An important thing that distinguishes a expert as distinct from an owner is that you encourage the expert to devote some of their time to helping others work in their discipline. # |

|

That we needed to give people slack time like that to sustain the level of overall teamwork was a general principle. There were other ways in which we didn’t just wait for the streams to cross themselves. We injected sustaining energy into this system very intentionally. # |

|

Human beings are limited by their in-group. You feel psychological safety within your in group. You feel like you can experiment and learn new things within your in group. You can exercise curiosity about the people in your in-group and what they do. So we invested time in making people’s in-groups larger. Bootcamps were one of those ways: we forced people to work on other teams occasionally. Hack weeks were another institution that achieved similar ends. # |

|

A decade later, I can articulate what our organization’s principles were. I can explain the higher-level reasons we were doing bootcamps, or code reviews, or a million other things. This is a victory of being intentional and vocal about what our team values were. # |

|

It was important to us to articulate that elitism as an attitude was poison. To the contrary, we do windows here. If a ditch needs digging, our tech leads will line up to dig it. We also needed to create the strong expectation that you’d leave things in a better state as you messed with other people’s stuff. That made people overjoyed to have you messing with their stuff. # |

|

Let me leave you with a few things. # |

|

Inside and outside of tech the world is rife with cult leaders who lack the gene for

humility - bullies who inspire and encourage cruelty in their followers to no end other nihilism. At a certain genetic equilibrium, NPD is evolutionarily adaptive, so these people are out there. But in tech we’ve grown a tendency to see it as useful rather than parasitic. The industry believes in assholes. Valuing others around you should not be a radical act, but that’s where things are unfortunately. # |

|

It shouldn’t be a radical act because results are better if we can cooperate. And life is better without cult leaders. How do we tear down parochialism and ego? # |

|

I’ve tried. I’ve got some notes about trying. Yes, growth hacking is a bad word and everything. But I have started growth teams twice and the one weird trick to making marketing start to work is to … try to help? It’s crazy. I inherited a situation where SRE was doing all of the deploys for the company, like it was the 90s. I pushed to switch that to developers shipping their own code. There was some hesitation, the worry being that developers would break stuff and not fix it. But the better angels of our nature prevailed, engineers largely resolved their own incidents right away. Product engineers actually asked to be handed the pagers! It was heartwarming. # |

|

The missing ingredient in those situations was just permission. Mainly what I needed to do was give people the permission they needed to be curious, and to cooperate. I don’t think you can grass roots that, beyond what I’m trying to do here by making the idea more popular. It’s on leaders to value cooperation and to reward curiosity. # |

|

In addition to permission, there has to be slack in the system. This requires persistent commitment. When you start skipping the bootcamps, they’ll die out as a practice. We don’t let our machines run at 100% utilization. But again, we have a tendency to love our computers more than ourselves. # |

|

The things we value and reward as leaders trickle down. Leaders can reward our worst or

our best impulses. Most CEO’s I’ve worked for have tried to kill feel-good programs like bootcamps and hack weeks, but I’ve never worked for a CEO that tried to end feel-bad programs like mandatory code review. None of them would admit this, but I think there’s an industry instinct that misery gets results. I think this is mistaken. Misery is a shitty proxy metric for results. # |

|

# |